This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Mass layoffs, social media bias and AI lawsuits: Experts discuss the state of the Fourth Estate

A wave of layoffs at high-profile legacy media outlets such as the Los Angeles Times and Time magazine has rippled across the news industry just as journalists at other major outlets are engaged in union negotiations with their employers. The industry seems to have reached a pivotal point amid a confluence of financial, political, social and technological challenges.

USC experts list a few of the forces steering the industry into new frontiers: a highly polarized presidential race; a media ecosystem clouded by fake news, propaganda and extremism; the influence of social media and tech companies on news visibility and ad revenues; and a debate over free speech versus hate speech, which can drive journalists and their followers to abandon one platform for another.

Add to this list widespread uncertainty about the impact of generative artificial intelligence on content and copyright, and it seems like American news, at least as we used to know it, has been upended. What it means for readers, the news industry and for the country remains to be seen, but Christian Phillips of the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences has some guesses.

"Cuts to news staffing levels in media markets across the country will mean that voters will have fewer options for local, high-quality journalism they have confidence in," said Phillips, assistant professor of political science. "In a period when voters are already having doubts about where to go for trustworthy information, that is troubling."

State of the media: Changing times

Perhaps, though, consumers just hold on too tightly to what newspapers and magazines used to be. Gordon Stables believes change in the news business is inevitable.

"There is unfortunately a nostalgia about a moment when newspapers had almost a monopoly on exposure," said Stables, director of the School of Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. "Since then, there has been a lot of creativity and a lot of exploration in media. It does, however, create boom-bust cycles."

Stables noted that, for example, Sports Illustrated, which recently laid off much of its staff, "used to be a much different magazine" since its founding in 1954 and onward through the 1990s. Historically, it highlighted strong feature writing by the likes of Frank Deford, Bill Russell, and before them, John Steinbeck and Carl Sandburg. It was an institution of impeccable storytelling, and it was popular.

In more recent years, though, the magazine has been overshadowed by other new digital sports outlets, an influx of sports talk shows both on radio and TV, plus new social and video platforms that feed consumers' seemingly insatiable appetite for news and engagement.

"Many of us had a lot of nostalgia for the Sports Illustrated that we knew when we were younger," Stables said. "But the reality is that as a brand, Sports Illustrated has not been the magazine that we knew in a long time."

The advancement of the internet and social media in recent decades has driven legacy media toward innovation, and coincidentally, greater opportunity for the emergence of new media.

The Los Angeles Times is navigating the same storm. Stables mentioned that the internationally recognized newspaper has tried several strategies to keep up with readers and their preferences.

Some tactics may have worked better in a pandemic, though. "They invested in a podcast studio," Stables noted.

At the same time, new digital outlets appeared and started giving California's paper of record a run for its money. Gabriel Kahn of USC Annenberg believes that is where the paper has lost ground.

"As the L.A. Times in recent years has failed to stake a claim to California, others, like CalMatters and Politico, have come in to pick up the slack," said Kahn, professor of professional practice of journalism. "That leaves less space for the Times to operate, which is a lost opportunity."

A fragile relationship

News media and technological innovations have shaped and influenced each other for centuries. Each holds the power to both harm and help the other in terms of audience, revenue and political leverage.

The field of digital news competitors has increased at the same time the public's trust in news has weakened, based on a Gallup survey released last October. These trends parallel a proliferation of fake news and conspiracy theories, some of which appear in the form of "deepfake" videos that are doctored to and mislead an audience about an event or what a politician said.

Social media platforms can boost truth or lies, which clouds the media ecosystem with a mix of well-researched and reported news with false narratives. The results depend on the platforms' algorithms and on their users. The algorithms generally are constructed to elevate any content promoted by habitual users even if the content they share is fake, researchers at USC Dornsife and the USC Marshall School of Business found in a study last year.

A sweeping solution has yet to be implemented.

"Despite the introduction of some fact-checking systems on select social media platforms, there is still insufficient regulation of fake news," said Kristen Schiele, associate professor of clinical marketing at USC Marshall.

Another point of tension for social media and the news industry: The social media companies don't pay any sort of copyright fee for any of the news shared on their sites—at least not in the United States. A similar issue has happened with generative AI companies, which have used news articles and other content available across the web to train their AI. They haven't had to pay for the content or give credit, which The New York Times is challenging in court.

"Do AI companies even need permission to do this? The recent lawsuit filed by The New York Times against OpenAI and Microsoft aims to answer this question, at least in part," said Jeffrey Pearlman, a clinical associate professor of law and director of the Intellectual Property and Technology Law Clinic at the USC Gould School of Law.

He continued, "There is an array of parallel lawsuits aimed at this and other aspects of generative AI, which may come to conflicting conclusions. But given the proliferation of generative AI and the challenges already faced by modern journalism, this lawsuit is surely one of the most important to watch."

A degree and profession worth pursuing

The recent layoffs and the uncertainty of the news business should not deter students from either pursuing journalism degrees or journalism jobs, USC Annenberg's Stables said. The opportunities in journalism and communication are evolving, he said, including some that do not follow the traditional news model that depends on ad revenues, which Big Tech also competes for.

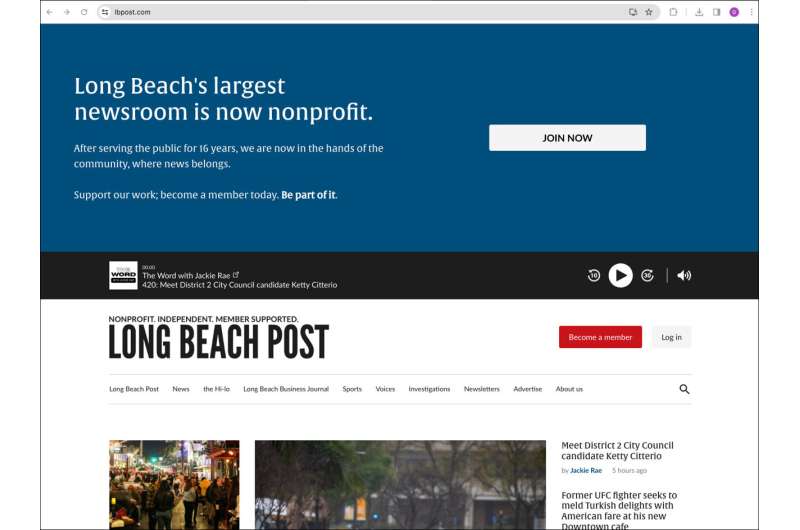

"We are seeing a lot more experimentation," Stables said. "The Long Beach Post is a good example of an outlet that moved to a nonprofit model. You see lots of other models that are entrepreneurial and that are growing."

Stables noted that many USC Annenberg graduates wind up selling their own documentaries, adding, "Some end up working at TV stations around the country. We have a lot of students who are successful in cross-platform video production.

"There is value in a journalism education, regardless of what your professional goals are. Our view is there is more interest and there is more need for journalism as long as people are willing to think more broadly about the opportunities—documentary, text and audio storytelling, for instance."

Provided by University of Southern California