This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Cold-water coral found to trap itself on mountains in the deep sea

Corals searching for food in the cold and dark waters of the deep sea are building higher and higher mountains to get closer to the source of their food. But in doing so, they may find themselves trapped when the climate changes.

That possibility is illustrated in the thesis that theoretical ecologist Anna van der Kaaden of NIOZ in Yerseke and the Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development in Utrecht will defend on Feb. 20 at the University of Groningen.

"When the water gets warmer, these creatures prefer to be deeper, but a coral doesn't just walk down the mountain," Van der Kaaden said.

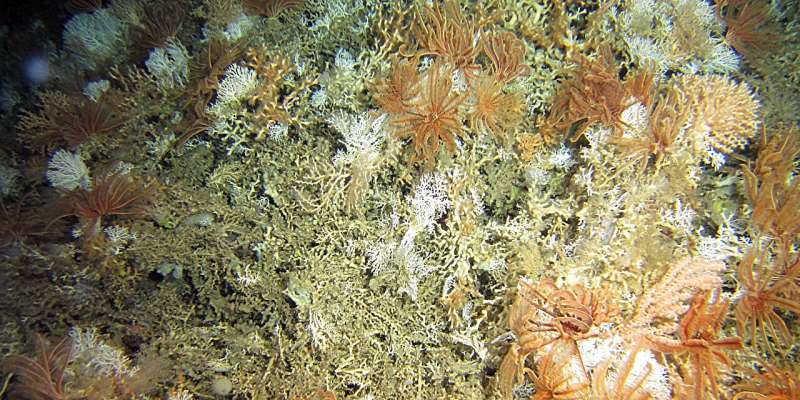

Unlike the famous, colorful tropical corals, cold-water corals live in dark waters a few hundred meters deep, for example, off the west coast of Ireland. In the dark, they do not coexist with algae, which often gives tropical corals their spectacular colors; after all, those algae need light.

"But that certainly does not mean that cold-water corals are boring," Van der Kaaden emphasizes. "They sometimes have beautiful colors of their own. And they certainly play an equally important role in the ecosystem as tropical reefs. For example, they are oases of food for fish. They have a very central place in the ocean systems."

Van der Kaaden conducted research on real reefs and on 'mathematical reefs' in computational models.

"In both cases, I tried to discover the spatial patterns in which the corals grow. With the Australian Great Barrier Reef, for example, this is very simple: You can even see their growth patterns from space. With cold-water corals, you have to recognize these patterns while walking around in a pitch-dark maze, so to speak, with only a small flashlight. And yet, using statistical techniques and video stills, we did manage to get an overall picture," she notes. Her thesis describes, among other things, the regular reefs, ridges and mountains that corals form over thousands of years.

Higher than the Eiffel Tower

Van der Kaaden also saw how the corals, as true "ecosystem engineers," adapted their environment, especially the water current, to attract more food particles to themselves.

"Over hundreds of thousands of years, the coral reefs form mountains that can grow higher than the Eiffel Tower. So, the corals get higher in the ocean, where there is more food, and those mountains also create water currents that transport the food to the mountain," she observes.

The expectation is that if the water becomes too warm due to climate change, the corals will want to grow lower and colder. Van der Kaaden explains, "A cold-blooded animal like a coral uses up too much energy in warmer water. But a coral is an animal that is attached to the bottom, so it can't just move down the mountain. It disperses through larvae, but for new corals, the food conditions on the flanks of a coral mountain are worse because of the specific flow patterns."

Van der Kaaden does not want to sound an immediate alarm about the survival of cold-water corals under the changing climate.

"Maybe these organisms are more resilient than we think, and if not, they might build new mountains or reefs in other places. But with this research, I do want to show that an organism's response to climate change is not always easy to predict. There are many complex processes that create unexpected obstacles or opportunities. We, as a society, must take that into account when preparing for the effects of climate change," she concludes.

More information: Anna van der Kaaden, Patterns in the deep sea, University of Groningen (2023). DOI: 10.33612/diss.846331043

Provided by Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research