This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

proofread

Using smart materials to deploy a Dark Age explorer

One of the most significant constraints on the size of objects placed into orbit is the size of the fairing used to put them there. Large telescopes must be stuffed into a relatively small fairing housing and deployed to their full size, sometimes using complicated processes. But even with those processes, there is still an upper limit to how giant a telescope can be. That might be changing soon, with the advent of smart materials—particularly on a project funded by NASA's Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC) that would allow for a kilometer-scale radio telescope in space.

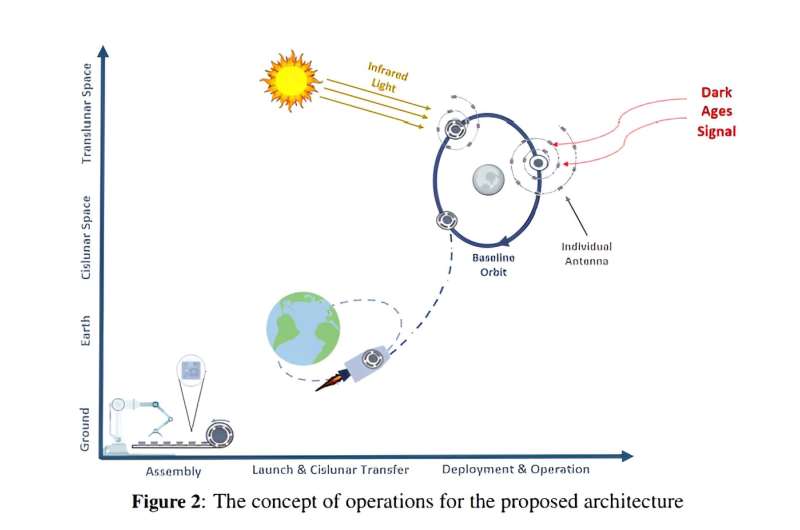

The project, headed by Davide Guzzetti at Auburn, would utilize self-folding smart polymers to deploy a series of radio antennas in a spiral pattern in space. Scientists could then use interferometry, a technique where signals that hit different dishes spread apart are used to amplify the effective area of the telescope.

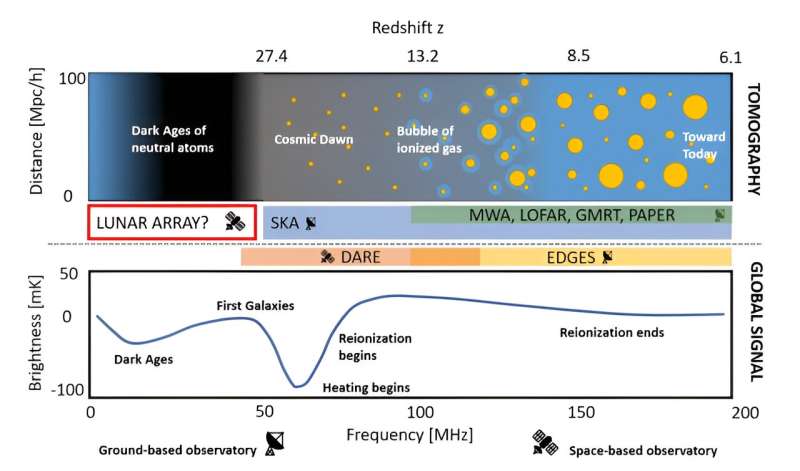

This telescope might be particularly good at searching for one thing—the 21-cm signal. A kind of holy grail of astrophysics, this signal was emitted during the early lives of hydrogen and is critical to understanding what happened between the Big Bang and the Era of Reionization in the early universe.

Unfortunately, the signal reaches Earth at relatively low frequencies, which are then filtered out by our ionosphere and, in some cases, interrupted by our own radio emissions. So various teams have suggested solutions to this. We've reported before on the idea of a telescope on the far side of the moon. Other projects include swarms of separated telescopes in space that again use interferometry but would be separate from one another.

While great, a telescope on the moon would require an infrastructure there to build and operate it, which obviously doesn't exist yet. On the other hand, telescopes set up in an interferometer configuration but not physically connected and just floating in space can change relative location, making maintaining that arrangement particularly challenging.

Dr. Guzzetti and his co-authors think they have a solution—set up an interferometer with dozens of tiny sensors but have them tied together by a smart material that can deploy after they are in space. In this scenario, you get the benefits of the large effective area of an interferometer without the need to have complicated correction algorithms for relative satellite position. Nor would you need to set up an entire infrastructure on the moon to operate it—it could be built with modern technology that already has a relatively high level of development.

In a paper released in 2021, the team describes how this system might work, including using a series of "ink hinges" that can introduce folding in a material once it reaches a specific temperature. Since exposure to direct sunlight would undoubtedly make it hit that temperature (100°C), an array of sensors with these hinges strategically placed between them could expand into a spiral pattern that could be kilometers in diameter.

That's a pretty good surface area for an interferometer. And the sensors can all be tied together using wires or similar connections run over the hinges, eliminating the problem that plagues other in-space interferometers with disconnected components.

While the system has its advantages, and the paper describes a method by which it could be deployed, there isn't any clear follow-up on the next steps for the project. The shape-memory polymers used in the system also have myriad other uses, so making a giant telescope in space might not be the highest priority for researchers who specialize in it. But, as with all ideas, it's worth noting and remembering that, maybe someday, we could have a kilometer-wide telescope floating above the Earth, picking up traces of the early universe.

Provided by Universe Today