This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Researchers use quantum computing to predict gene relationships

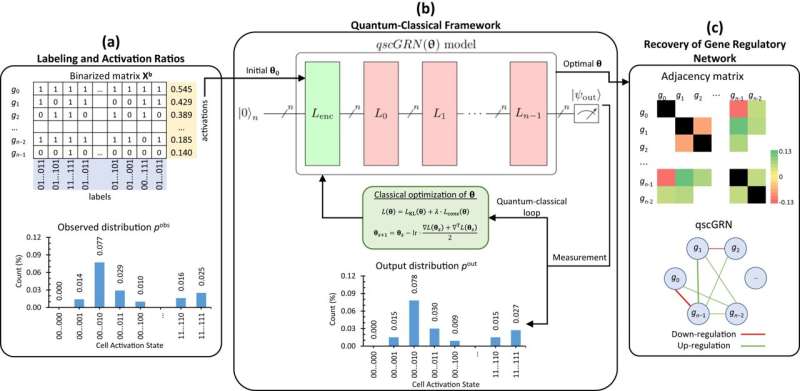

In a new multidisciplinary study, researchers at Texas A&M University showed how quantum computing—a new kind of computing that can process additional types of data—can assist with genetic research and used it to discover new links between genes that scientists were previously unable to detect.

Their project used the new computing technology to map gene regulatory networks (GRNs), which provide information about how genes can cause each other to activate or deactivate.

As the team published in npj Quantum Information, quantum computing will help scientists more accurately predict relationships between genes, which could have huge implications for both animal and human medicine.

"The GRN is like a map that tells us how genes affect each other," Cai said. "For example, if one gene switches on or off, then it may change another gene that could change three, or five, or 20 more genes down the line."

"Because our quantum computing GRNs are constructed in ways that allow us to capture more complex relationships between genes than traditional computing, we found some links between genes that people hadn't known about previously," he said. "Some researchers who specialize in the type of cells we studied read our paper and realized that our predictions using quantum computing fit their expectations better than the traditional model."

The ability to know which genes will affect other genes is crucial for scientists looking for ways to stop harmful cellular processes or promote helpful ones.

"If you can predict gene expression through the GRN and understand how those changes translate to the state of the cells, you might be able to control certain outcomes," Cai said. "For example, changing how one gene is expressed could end up inhibiting the growth of cancer cells."

Making the most of a new technology

With quantum computing, Cai and his team are overcoming the limitations of older computing technologies used to map GRNs.

"Prior to using quantum computing, the algorithms could only handle comparing two genes at a time," Cai said.

Cai explained that only comparing genes in pairs could result in misleading conclusions, since genes may operate in more complex relationships. For example, if gene A activates and so does gene B, it doesn't always mean that gene A is responsible for gene B's change. In fact, it could be gene C changing both genes.

"With traditional computing, data is processed in bits, which only have two states—on and off, or 1 and 0," Cai said. "But with quantum computing, you can have a state called the superposition that's both on and off simultaneously. That gives us a new kind of bit—the quantum bit, or qubit.

"Because of superposition, I can simulate both the active and inactive states for a gene in the GRN, as well as this single gene's impact on other genes," he said. "You end up with a more complete picture of how genes influence each other."

Taking the next step

While Cai and his team have worked hard to show that quantum computing is helpful to the biomedical field, there's still a lot of work to be done.

"It's a very new field," Cai said. "Most people working in quantum computing have a physics background. And people on the biology side don't usually understand how quantum computing works. You really have to be able to understand both sides."

That's why the research team includes both biomedical scientists and engineers like Cai's Ph.D. student Cristhian Roman Vicharra, who is a key member of the research team and spearheaded the study behind the recent publication.

"In the future, we plan to compare the healthy cells to ones with diseases or mutations," Cai said. "We hope to see how a mutation might affect genes' states, expression, frequencies, etc."

For now, it's important to get as clear an understanding as possible of how healthy cells work before comparing them to mutated or diseased cells.

"The first step was to predict this baseline model and see whether the network we mapped made sense," Cai said. "Now, we can keep going from there."

More information: Cristhian Roman-Vicharra et al, Quantum gene regulatory networks, npj Quantum Information (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41534-023-00740-6

Journal information: npj Quantum Information

Provided by Texas A&M University