This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Non-native diversity mirrors Earth's biodiversity: Study highlights potential for future waves of invasive species

Human trade and transport have led to the intentional and accidental introductions of non-native species outside of their natural range globally. These biological invasions can cause extinctions, cost trillions, and spread diseases. A study from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, now published in Global Ecology and Biogeography, has investigated how many of these non-native species already exist worldwide and which species groups are particularly prone to become non-native.

"Everything that exists can be introduced somewhere at some point," says Dr. Elizabeta Briski. The marine biologist is an expert in invasion ecology at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel. Along with a large international team of renowned ecologists, she has conducted a study to investigate whether non-native species mirror Earth's patterns of biodiversity and found that greater numbers of non-native species tend to come from more diverse species groups.

Briski says, "Biological invasions can cause extinctions, cost trillions of dollars in damage and control, and spread diseases." But that is not necessarily the case, which is why Briski prefers a neutral term "non-native species" instead of "invaders." And their numbers are growing rapidly, making large-scale understandings and predictions of invasion patterns crucial to protect environments, economies, and societies.

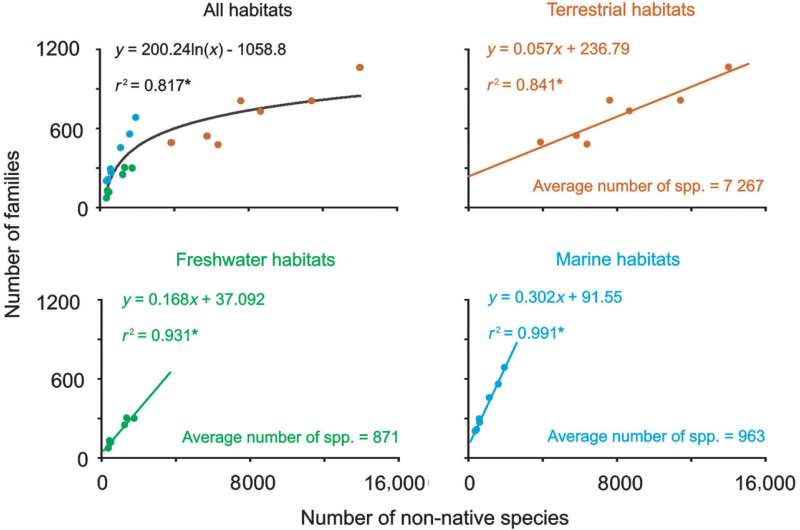

"We investigated whether the number of non-native species reflects patterns in global biodiversity. We then looked at whether certain groups of species are disproportionately prone to establish in new areas." To do this, the researchers compiled a comprehensive list of non-native species described to date—there are around 37,000 worldwide—and grouped them according to biological taxonomy—from phyla to classes and families.

Then, they put them in relation to global biodiversity. The result: whether microscopically small or the size of a hippopotamus, whether on land or under water—on average about 1% of all living organisms have been transported by humans somewhere in the world.

"Of course, the data situation varies greatly in some cases," Briski points out. Species on land are generally better studied than those in the water. A greater research effort would therefore probably uncover a significant number of new non-native species in marine habitats.

Other understudied groups, such as microorganisms, are also likely to be vastly underestimated in non-native species inventories. In addition, richer countries tend to have more research on non-native species than poorer countries. "It is therefore quite possible that there are many non-native species in the tropical rainforest that we simply don't know about."

The researchers found that some groups have excessively established outside their native range, including mammals, birds, fishes, insects, spiders, and plants. Briski says, "The most commonly reported introduced non-native species tend to be those that have been introduced intentionally for agriculture, horticulture, forestry or other purposes." And unwanted species always come along with the wanted ones, for example as stowaways on ships. "Nobody wanted to introduce rats, but they have spread across the globe alongside humans," says Briski.

Overall, the results indicate a huge potential for future biological invasions in various species groups. Briski says, "If only one percent of global biodiversity has been affected so far, we can assume that the extent will increase considerably." The randomness of the process is remarkable. "Sooner or later, any species can use our transport manners and routes to reach areas to which it would not naturally have access."

The magnitude of environmental and socio-economic impacts due to new invasions is thus likely to rise substantially in the coming decades, particularly as trade and transport accelerate and shift, connecting distant countries and their unique species pools. Briski and colleagues call for urgent action to prevent future introductions and to control the most damaging invaders that are already established.

More information: Elizabeta Briski et al, Does non‐native diversity mirror Earth's biodiversity?, Global Ecology and Biogeography (2023). DOI: 10.1111/geb.13781

Journal information: Global Ecology and Biogeography

Provided by Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres