This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

written by researcher(s)

proofread

Wild bird feeding surged worldwide during lockdowns. That's good for people, but not necessarily for the birds

Feeding wild birds in backyards was already known to be extremely popular in many parts of the northern hemisphere and in Australia, despite being strongly discouraged. But the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns led to a dramatic increase in wild bird feeding around the world, our research published today shows. There was a surge in interest beyond traditional bird-feeding countries in North America, Europe and Australia: 115 countries in total, including many where feeding was assumed not to occur.

Those opposed to feeding wild birds cite a plethora of reasons:

- the spread of diseases (well-documented in the US and UK)

- poor nutrition as a result of an unbalanced diet

- advantaging already abundant species

- changing community structure (birds that visit feeders prosper at the cost of those that don't)

- even altering migration patterns.

These impacts occur everywhere wild birds are fed and are potentially serious.

On the other hand, engaging with wild birds in this way is now recognized as one of the most effective ways people can connect with nature. There is strong evidence that spending time in natural settings is good for people's well-being and mental health. This becomes increasingly important as more and more of the world's people live in large cities.

These trends mean the simple, common practice of attracting birds to your garden by feeding them is taking on much greater significance for the welfare of both birds and people.

What did the study look at?

Previous studies documented a global increase in birdwatching during lockdowns. We wondered whether interest in feeding birds might have increased similarly as well. That usually means buying seed mixes and providing a feeder. To be included in our study, some cost was required; discarded food scraps were not counted as feeding.

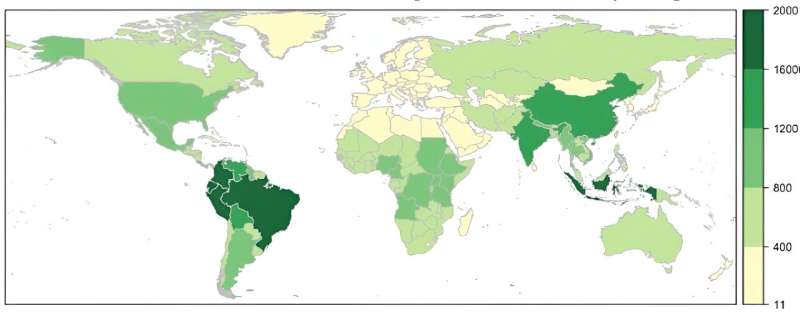

It was important to go beyond the countries where we already knew feeding was common. We wanted to compare the interest levels for more than 100 countries during and after lockdowns. We also examined whether the level of interest in bird feeding was related to the diversity of birds in each country, a measure known as "species richness."

We assessed the weekly frequency of search terms, including "bird feeder," "bird food" and "bird bath," using Google Trends for all countries with sufficient search volumes from January 1 2019 to May 31 2020. We wanted to see if these searches increased during each country's specific lockdown period (generally around February–April 2020). We drew on bird species richness data for each nation from the BirdLife International database.

Comparing the interest volume for 52 weeks leading up to the lockdown with the week immediately before, we found no discernible change. Within only two weeks, however, the frequency of searches showed a surge in bird feeding interest during the general lockdown period across 115 of the countries surveyed. This happened in both the northern and southern hemispheres.

What explains the change?

There are several possible reasons for this change. People throughout the world were forced to remain close to home. The backyard or nearby park became the focus of attention, perhaps for the first time.

Lockdowns were a time of high anxiety and stress. Aspects of life that seemed to be carrying on regardless, such as birds arriving each day to be fed, may have been a course of comfort and reassurance.

Feeding birds has been found to enhance feelings of personal worth and peace. Presumably, it's because of the relative intimacy associated with being able to attract wild, unrestrained creatures to visit by simply providing some food.

Bird feeding is also cheap, simple and available to virtually everyone. Birds will visit a feeder in a private garden, a public park or even a balcony on a residential tower.

And what difference does bird diversity make?

We found a clear association between the level of interest in feeding and species diversity. Countries that lacked bird-related search interest had an average of 294 bird species. In contrast, those countries with clear interest had an average of 511 species.

This clear difference suggests that having a greater variety of species prompts more bird feeding. It may also mean places with more species have a larger number of bird types living in their cities (where most feeders live). This remains to be be investigated. We do know that feeding birds leads to more birds overall, but not more species.

Because we used Google searches as the proxy measurement for bird-feeding interest, bird-feeding practices in countries with lower income or less internet access may not have been adequately captured. Nonetheless, our method was able to detect a surge of interest in bird feeding in countries such as Pakistan and Kenya.

The COVID-19 lockdowns seemed to encourage people all over the world to seek connection and interaction with their local birds. We hope future studies can further analyze the global extent of bird feeding and capture more data in previously understudied countries.

Feeding birds is obviously very popular. For people. But it can lead to problems for the birds. To minimize the risks, keep in mind some simple rules:

- keep the feeder extremely clean (disease is always a concern)

- don't put out too much food (they don't need it)

- provide food that is appropriate for the species (never human food—buy wild bird food from pet food companies).

More information: Jacqueline Doremus et al, Covid-related surge in global wild bird feeding: Implications for biodiversity and human-nature interaction, PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0287116

Journal information: PLoS ONE

Provided by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()