This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies. Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

proofread

Water-purifying cup makes drinkable water from creeks and streams

A rash of storms in Texas in recent years—from Hurricane Harvey in 2017 to the deep freeze in 2021—has put big chunks of the population in danger and left millions without electricity or water for long periods.

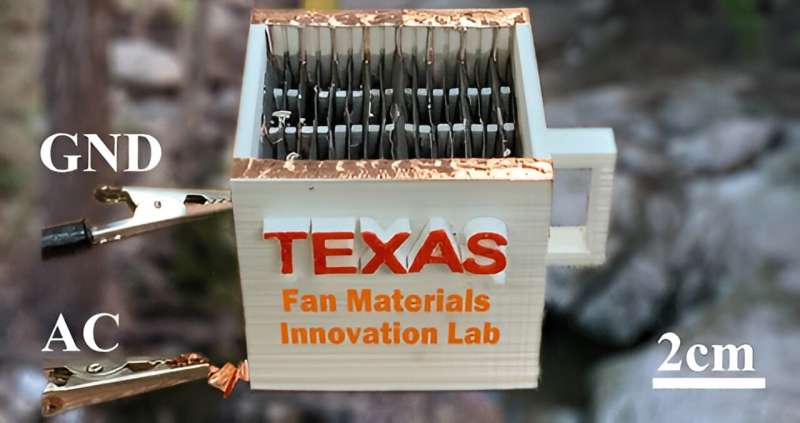

These calamities have also served as motivation for a researcher at The University of Texas at Austin to refocus her work on innovations that can help communities respond to severe weather events. Her latest project is a mug-sized device that can quickly clean water using a small jolt of electricity to fish out bacterial cells. In lab experiments, the device was able to remove 99.997% of E. coli bacteria from 2- to 3-ounce samples taken from Waller Creek in Austin in approximately 20 minutes, with the capacity to do more.

"We are able to clean water using very little energy because we steer the bacterial cells with electric fields, and most bacterial cells are natural swimmers who propel themselves to electrodes and got captured alive," said D. Emma Fan, an associate professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering's Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering, who led the research published recently in ACS Nano.

The key to the device is a "branched" electrode that the research team previously created. The patented electrode's structure is based on a root system in a tree with branches traveling in several directions.

When electrified, the device creates a field to which the E. coli cells are attracted. They willingly "swim" into the electrode branches.

The electrode is made of graphite foam, compatible and durable in electric fields, and can continuously work for many hours. In addition to its efficiency, the device is inexpensive—it costs less than $2 to create the foam-encased electrode.

It also is simple to use. First, dip the electrode-filled cup into water. Next, give it an electrical jolt, wait, and let the electrodes fish out bacteria. Then, wait and remove the water, which is now drinkable.

The researchers are now looking into ways to commercialize it and next want to streamline the design of the cup. The one used to clean water from Waller Creek is a 3D-printed prototype. The team wants to further simplify the process of inserting and removing the electrodes.

Of the several different current methods for simple, commercial water filtration, each has a significant flaw. Disinfecting pills can release oxidants that can be harmful if ingested. Reverse osmosis systems require high water pressure, and solar steaming needs consistent sunlight, which is unreliable amid natural disasters.

Furthermore, the use of electrical power allows integration with batteries for stored energies and can be easily used at home, in the office, or in a car. The energy cost is also much less than those of various emerging technologies, e.g., a thousandth as much as that for solar steaming.

The electrode used in the device was originally created for supercapacitors. Estimates that Texas's population would double by 2050 and the need for research to address resilience after Harvey motivated Fan to focus her work on natural disasters.

In the case of a power outage or a boil-water notice, a person who owned a device with this technology could drive to a creek or a stream, hook it up to the car battery through a simple DC-AC converter, and purify water to bring home as a drinking supply. It can also be powered using solar panels with the same principle.

"When our water infrastructure is down—no water, no gas and no electricity—we need point-of-use devices for cleaning water we can get out of ponds, streams or rivers," Fan said. "We believe our device can someday fill that need."

More information: Xianfu Luo et al, Portable Bulk-Water Disinfection by Live Capture of Bacteria with Divergently Branched Porous Graphite in Electric Fields, ACS Nano (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.2c12229

Journal information: ACS Nano

Provided by University of Texas at Austin