Ancient grammatical puzzle solved after 2,500 years

A grammatical problem that has defeated Sanskrit scholars since the 5th century BC has finally been solved by an Indian Ph.D. student at the University of Cambridge. Rishi Rajpopat made the breakthrough by decoding a rule taught by "the father of linguistics," Pāṇini.

The discovery makes it possible to "derive" any Sanskrit word—to construct millions of grammatically correct words including "mantra" and "guru"—using Pāṇini's revered "language machine," which is widely considered to be one of the great intellectual achievements in history.

Leading Sanskrit experts have described Rajpopat's discovery as "revolutionary" and it could now mean that Pāṇini's grammar can be taught to computers for the first time.

While researching his Ph.D. thesis, published today, Dr. Rajpopat decoded a 2,500 year old algorithm that makes it possible, for the first time, to accurately use Pāṇini's "language machine."

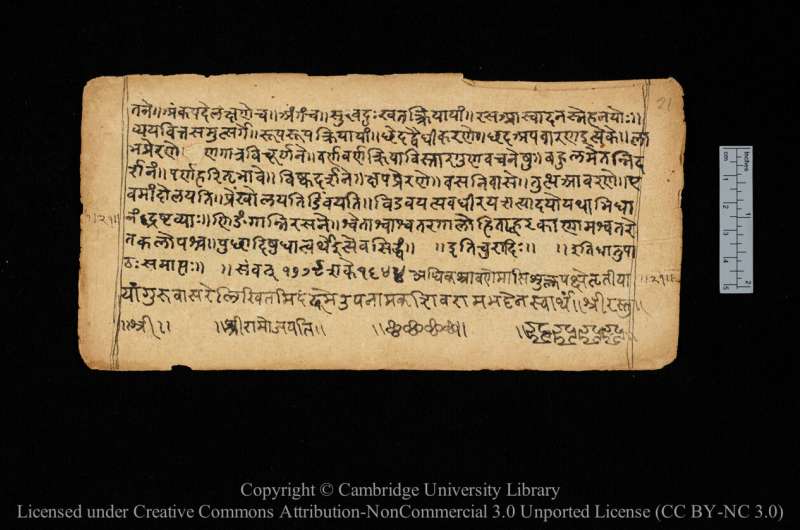

Pāṇini's system—4,000 rules detailed in his greatest work, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, which is thought to have been written around 500 BC—is meant to work like a machine: Feed in the base and suffix of a word and it should turn them into grammatically correct words and sentences through a step-by-step process.

Until now, however, there has been a big problem. Often, two or more of Pāṇini's rules are simultaneously applicable at the same step, leaving scholars to agonize over which one to choose.

Solving so-called "rule conflicts," which affect millions of Sanskrit words including certain forms of "mantra" and "guru," requires an algorithm. Pāṇini taught a metarule to help us decide which rule should be applied in the event of "rule conflict," but for the last 2,500 years, scholars have misinterpreted this metarule, meaning that they often ended up with a grammatically incorrect result.

In an attempt to fix this issue, many scholars laboriously developed hundreds of other metarules, but Dr. Rajpopat shows that these are not just incapable of solving the problem at hand—they all produced too many exceptions—but also completely unnecessary. Rajpopat shows that Pāṇini's "language machine" is self-sufficient.

Rajpopat said, "Pāṇini had an extraordinary mind and he built a machine unrivaled in human history. He didn't expect us to add new ideas to his rules. The more we fiddle with Pāṇini's grammar, the more it eludes us."

Traditionally, scholars have interpreted Pāṇini's metarule as meaning that in the event of a conflict between two rules of equal strength, the rule that comes later in the grammar's serial order wins.

Rajpopat rejects this, arguing instead that Pāṇini meant that between rules applicable to the left and right sides of a word respectively, Pāṇini wanted us to choose the rule applicable to the right side. Employing this interpretation, Rajpopat found Pāṇini's language machine produced grammatically correct words with almost no exceptions.

Take "mantra" and "guru" as examples. In the sentence "Devāḥ prasannāḥ mantraiḥ" ("The Gods [devāḥ] are pleased [prasannāḥ] by the mantras [mantraiḥ]") we encounter "rule conflict" when deriving mantraiḥ "by the mantras." The derivation starts with "mantra + bhis." One rule is applicable to left part, "mantra'," and the other to right part, "bhis." We must pick the rule applicable to the right part, "bhis," which gives us the correct form, "mantraiḥ."

In the the sentence "Jñānaṁ dīyate guruṇā" ("Knowledge [jñānaṁ] is given [dīyate] by the guru [guruṇā]") we encounter rule conflict when deriving guruṇā "by the guru." The derivation starts with "guru + ā." One rule is applicable to left part, "guru" and the other to right part. "ā". We must pick the rule applicable to the right part, "ā," which gives us the correct form, "guruṇā."

Eureka moment

Six months before Rajpopat made his discovery, his supervisor at Cambridge, Vincenzo Vergiani, Professor of Sanskrit, gave him some prescient advice: "If the solution is complicated, you are probably wrong."

Rajpopat said, "I had a eureka moment in Cambridge. After 9 months trying to crack this problem, I was almost ready to quit, I was getting nowhere. So I closed the books for a month and just enjoyed the summer, swimming, cycling, cooking, praying and meditating. Then, begrudgingly I went back to work, and within minutes, as I turned the pages, these patterns starting emerging, and it all started to make sense. There was a lot more work to do but I'd found the biggest part of the puzzle."

"Over the next few weeks I was so excited, I couldn't sleep and would spend hours in the library, including in the middle of the night to check what I'd found and solve related problems. That work took another two and half years."

Significance

Professor Vincenzo Vergiani said, "My student Rishi has cracked it—he has found an extraordinarily elegant solution to a problem which has perplexed scholars for centuries. This discovery will revolutionize the study of Sanskrit at a time when interest in the language is on the rise."

Sanskrit is an ancient and classical Indo-European language from South Asia. It is the sacred language of Hinduism, but also the medium through which much of India's greatest science, philosophy, poetry and other secular literature have been communicated for centuries. While only spoken in India by an estimated 25,000 people today, Sanskrit has growing political significance in India, and has influenced many other languages and cultures around the world.

Rajpopat said, "Some of the most ancient wisdom of India has been produced in Sanskrit and we still don't fully understand what our ancestors achieved. We've often been led to believe that we're not important, that we haven't brought enough to the table. I hope this discovery will infuse students in India with confidence, pride, and hope that they too can achieve great things."

A major implication of Dr. Rajpopat's discovery is that now that we have the algorithm that runs Pāṇini's grammar, we could potentially teach this grammar to computers.

Rajpopat said, "Computer scientists working on natural language processing gave up on rule-based approaches over 50 years ago... So teaching computers how to combine the speaker's intention with Pāṇini's rule-based grammar to produce human speech would be a major milestone in the history of human interaction with machines, as well as in India's intellectual history."

The research is published in the journal Apollo—University of Cambridge Repository.

More information: Rishi Rajpopat, In Pāṇini We Trust: Discovering the Algorithm for Rule Conflict Resolution in the Aṣṭādhyāyī, Apollo—University of Cambridge Repository (2022). DOI: 10.17863/cam.80099

Provided by University of Cambridge