November 26, 2022 report

Skull and partial skeleton found in Morocco helps link ancient whale species

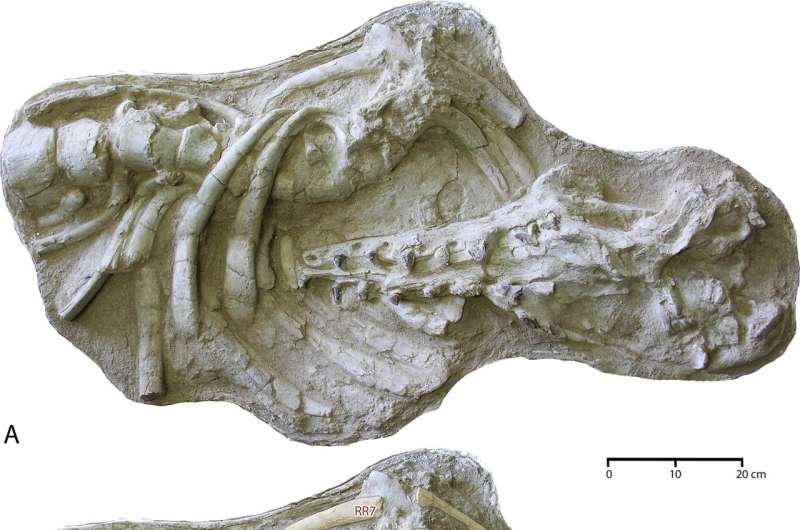

Three researchers, one with the University of Michigan, the other two with the University of Casablanca, have found a skull and partial skeleton in Morocco that they suggest link together several species of ancient whales. In their paper published in the open access journal PLOS ONE, Philip Gingerich, Ayoub Amane and Samir Zouhri describe the fossils and how they tie together the evolution of land-based creatures that evolved into modern whales.

The fossils found by the researchers were dated to approximately 40 million years ago (during the Eocene) and were identified as a member of Basilosaurid, a family of ancient whales that were land-based but had developed multiple aquatic adaptions, such as flippers. Prior research has shown they lived around what is now Africa, North America and Europe.

Eventually (over the ensuing 5 million years) they evolved to become modern whales. But the researchers noted differences in the fossils that connect several types of whales that belonged to the species Antaecetus, such as Pachycetus paulsonii and Pachycetus wardii. The differences were great enough to earn the fossil its own genus, Antaecetus aithai. The main trait that differentiated it from the others was its comparatively small skull.

The researchers note that members of the species were known to have thick, dense bones that hint at musculature, but they also suggest that they were relatively slow swimmers and not agile in the water. It has been theorized that because they were still evolving from land animals to sea creatures, it is likely they had a large lung capacity.

Taken together, such attributes suggest the species would likely have spent most of its time along the seafloor close to the shore. And they probably would have looked more like manatees than whales. One major difference between them and modern manatees, the researchers note, would have been their diet.

Modern manatees eat plants; Antaecetus species would have been predators, likely consuming slow-moving, soft-bodied creatures living on or near the sea bed. Thus, they likely would have had to catch their prey via ambush, rather than chasing them down.

More information: Philip D. Gingerich et al, Skull and partial skeleton of a new pachycetine genus (Cetacea, Basilosauridae) from the Aridal Formation, Bartonian middle Eocene, of southwestern Morocco, PLOS ONE (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276110

Journal information: PLoS ONE

© 2022 Science X Network