How to fight misinformation in the post-truth era

An article published in the Journal of Social Epistemology entitled "Institutions of Epistemic Vigilance: The Case of the Newspaper Press" authored by Central European University researchers Akos Szegofi and Christophe Heintz describe how we can and should fight against misinformation: through collective action. The fight can only be won through updating existing institutions of epistemic vigilance, argue the researchers, but not necessarily through updating the human mind.

Szegofi and Heintz show that the current era we sometimes refer to as "post-truth" is not without precedence: whenever communication environments change, speakers who want to deceive others and listeners who want to avoid being deceived are yet again entangled in an arms-race like mechanism. The latest stage of this is what we now call post-truth.

But how can listeners prevail in this arms race? How can they avoid being misled when there are so many new communicational platforms and methods to be deceived?

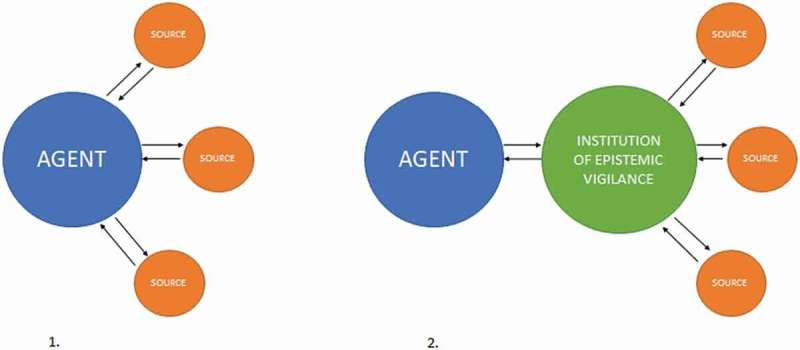

The authors claim that humanity has come up with a specific method: instead of evolving their brains to meet the requirements of the new communication environment, they evolve institutions to do the heavy lifting. These "institutions of epistemic vigilance" are organized in an analogous fashion to how some capacities of the brain work.

Instead of cells and neuronal pathways, the tasks are distributed among human individuals and non-human tools such as search engines and open-source investigative databases. Thus, when the task to curate information may be too much for a single individual to handle in our hectic Digital Age, institutions make it possible for them to do so anyways.

"While people have the psychological skills to exercise epistemic vigilance on their own, there are contexts where we benefit from trusting institutions with these tasks—for example in case of difficult but highly relevant medical information or filtering out relevant/irrelevant information," says Christophe Heintz.

Institutions are, however, fragile constructions that face several new challenges. A possible problem the authors point out is the fact that good epistemic practices are costly, and the expectation of gratis information from the internet forces the epistemic institutions to seek funds elsewhere, which might damage their impartiality and factuality.

A further difficulty is presented by social media platforms, where readers meet fake and truth in the same epistemic space. Simultaneous presentation "puts reliable information into an uneven competition: truth is insensitive to our preferences, while fakes are doctored to fit them. Thus, the psychological mechanisms of epistemic vigilance—that tend to modulate trust in light of the message source—are decreased in their efficiency," says Akos Szegofi.

The article also touches upon the question of the future usage of AI and the fear that it may be used to produce disinformation in the future. "The institutions of epistemic vigilance are indeed challenged by digitization. Perhaps the solution lies in digitization too, in programming AI to curate reliable information based on the principles of epistemic vigilance," the authors claim.

In conclusion, history tells us that institutions that deliver reliable information are fragile, and there is no straightforward strategy to repair them. Szegofi and Heintz believe that while it is not certain that we will have institutions of epistemic vigilance in the future, it is worth saving them, as they allow for us to trust.

More information: Ákos Szegőfi et al, Institutions of Epistemic Vigilance: The Case of the Newspaper Press, Social Epistemology (2022). DOI: 10.1080/02691728.2022.2109532

Provided by Central European University