Lost medieval chapel sheds light on royal burials at Westminster Abbey, finds new study on 15th-century reconstruction

New evidence, helping to form a 15th-century reconstruction of part of Westminster Abbey, demonstrates how a section of the building was once the focus for the royal family's devotion to the cult of a disemboweled saint and likely contained gruesome images of his martyrdom.

Findings, published in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association, reveal a story of how England's "White Queen" Elizabeth Woodville once worshiped at the Chapel of St. Erasmus, which may have even featured a whole, single tooth as part of the relics.

Today, only an intricate frame remains from the lost chapel of St. Erasmus. It was demolished in 1502 and little has been known about its role historically.

However, an extensive analysis of all available evidence to date, including a newly-discovered, centuries-old royal grant by the Abbey's archivist Matthew Payne, and John Goodall, a member of the Westminster Abbey Fabric Advisory Commission, reveal the chapel's wider importance.

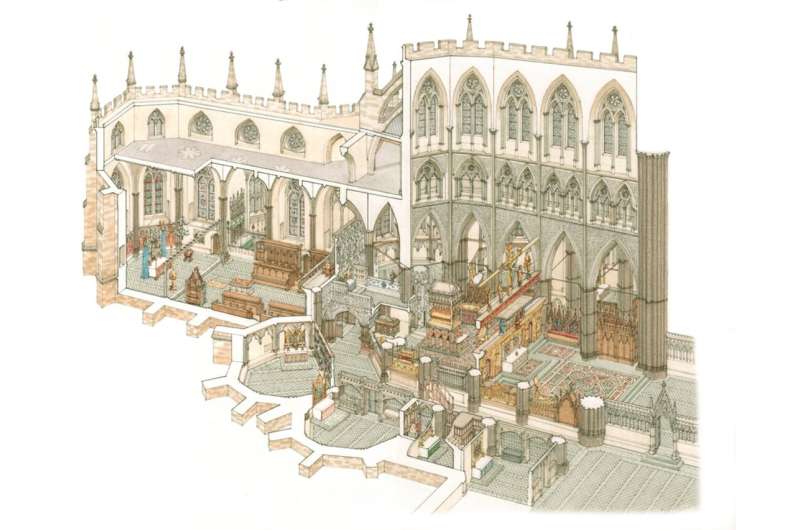

Evidence from the study has also helped to create a visual 15th-century reconstruction of the east end of the Abbey church and its furnishings, crafted by illustrator Stephen Conlin.

Commenting on the prominence of the chapel, Payne says. "The White Queen wished to worship there—and it appears—also to be buried there, as the grant declares prayers should be sung 'around the tomb of our consort (Elizabeth Woodville).' The construction, purpose and fate of the St. Erasmus chapel, therefore, deserves more recognition."

Goodall adds, "Very little attention has been paid to this short-lived chapel. It receives only passing mention in abbey histories, despite the survival of elements of the reredos. The quality of workmanship on this survival suggestions that investigation of the original chapel is long overdue."

The interment in the chapel of eight-year-old Anne Mowbray, child bride of Elizabeth's son Richard, Duke of York, also confirms its role as a royal burial site, their study finds.

In the end, Elizabeth's last resting place was next to her beloved husband in Windsor in St. George's Chapel, which Edward IV had begun in 1475. Future monarchs have also been buried in St. George's, including Elizabeth II after her funeral this year at the Abbey.

St. Erasmus was responsible for child well-being as well as being the patron saint of sailors and abdominal pain. The authors suggest his link with children may have prompted the building of the St. Erasmus chapel. It followed the wedding a year earlier, in 1478, of Anne Mowbray to Richard, when both were still infants.

Dedication of the chapel to St. Erasmus "reflects a new and rapidly growing devotion" to his cult, say the authors. They speculate that the building may also have held relics of the Italian bishop, namely his tooth, which Westminster Abbey is known to have owned.

Although the precise location is unknown, the chapel was almost certainly built on space formerly allotted to a garden and near stalls where William Caxton sold his wares, according to the authors.

Commissioned by Elizabeth, Edward IV's commoner wife and Henry VIII's grandmother, St. Erasmus's chapel was demolished in 1502. Visitors to Westminster Abbey can still view what remains, by looking above the entrance to the chapel of Our Lady of the Pew in the north ambulatory. What does remain is an intricately carved frame, sculpted out of the mineral alabaster. This frame would have surrounded a reredos, which is the imagery that forms the backdrop to the altar.

Missing, however, is the image. The study speculates that this was probably of the Saint being disemboweled—tied down alive to a table while his intestines were wound out on a windlass, a rotating cylinder often used on ships.

The screen would have originally been positioned behind the altar of the St. Erasmus chapel and contained a panel.

The study presents further evidence that the reredos was created by an outsider to the Abbey's design tradition. Architect Robert Stowell, the Abbey's master mason, probably designed the chapel itself and may have helped salvage the chapel's most ornate pieces when it was knocked down after less than 25 years.

This was on Henry VII's orders to make way for his own and his wife's chantry and burial place. The Lady Chapel that replaced it features a statue of St. Erasmus, which the authors say may be a nod to Elizabeth Woodville's now long-forgotten chapel.

More information: Elizabeth Woodville and the Chapel of St Erasmus at Westminster Abbey, Journal of the British Archaeological Association (2022). DOI: 10.1080/00681288.2022.2101237

Provided by Taylor & Francis